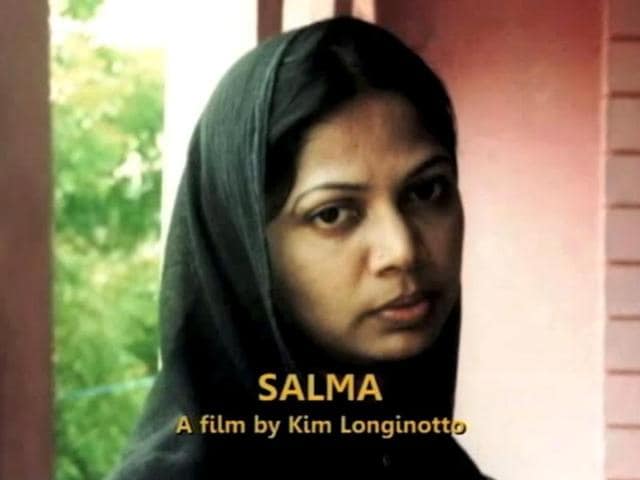

Salma: the woman who rebelled through poetry

Hindustan Times | Gautaman Bhaskaran, Chennai

Aug 24, 2014 02:21 PM IST

After watching the documentary, Salma, at least one similarity between its British filmmaker Kim Longinotto and the subject -- a Muslim woman from a small Tamil Nadu town is sure to hit the audience.

After watching the documentary, Salma, at least one similarity between its British filmmaker Kim Longinotto and the subject -- a Muslim woman from a small Tamil Nadu town is sure to hit the audience.

Salma’s home was as good as a jail. For quarter century, she was a prisoner of sorts in her home – first under her father and later her husband. Of course, Salma in the course of an interview at her Chennai flat, avers that it may not be the right thing to say that she was "locked up" – as was being stated in the 90-minute documentary on her. Yes, her freedom to go out of home unescorted by a male relative and the restriction placed on her freedom to write poetry can be termed incarceration. Her talent was not allowed to bloom, her desire to express herself through poems was curbed.

HT launches Crick-it, a one stop destination to catch Cricket, anytime, anywhere. Explore now!

But, then, this was the case with all other Muslim girls in her town. The picture was quite different, though, in cities, because they afforded anonymity and a sense of competitiveness prevailed. "How could you not let your own daughter attend school when your neighbourhood girls were being educated", Salma explains.

And, like Salma, who has penned some great poetry, even some daring verses, some fantastic short stories and even a gripping novel, -- some of these in the secluded secrecy of her bathroom-- and published them in little magazines, Kim grew up to be a renowned moviemaker – although no curbs were placed on her art by either her family or society.

Often described as an observational filmmaker, Kim’s cinema is direct and spontaneous. She does not plan anything, just watches her subject and shoots. Salma too has been observing the world for a long time, and her poetry reflects the pain and pathos of being a woman in her community.

She says that she – called Rajathi by her family – and her sister had only a small window with grills to look at the world outside. Sadly, the window faced a street which led to a cemetery, and hardly anybody walked by. Yet, that window in that room where the girls were confined most of the time – most certainly when men came visiting the family – was the source of light and life, a window that nudged and provoked Salma to dream of the freedom to write and for greater things.

But this was easier dreamt than done. At her village, Thuvarankurichi, in Tamil Nadu’s Tiruchirappalli district, Muslim girls were forbidden to step out of home once they attained puberty. Marriage hardly altered things, with the girls stepping from one kind of bondage to another, imposed this time by the husbands.

When Salma was barely 11, her marriage was fixed with a local boy, but she managed to ward off the actual wedding till she was 22. After this, she was confined to her husband’s home with a new name, Rokkaiah.

But the pangs of poetic hunger forced her out. She managed to frequent a public library and graduated from comics to magazines and Russian literature, Tolstoy and Dostoyevsky, among this. Her cousin smuggled in magazines, and Salma collected the bits of newspapers which were used to wrap groceries. Her verses – which she wrote under the name of Salma -- reached little magazines, but it was not until one of her poems was published with her photograph and name on the cover of a leading Tamil journal, Anantha Vikatan, in 2001 that her family and village woke up – not in appreciation, but in anger. Her husband threatened to immolate himself, always keeping a bottle of kerosene in his wardrobe. At other times, he would warn her that he would disfigure her face with acid. So Salma would sleep with her little son close to her face. She was sure that her husband would not harm him. Well, nothing happened.

Salma’s pluck prevailed and she not only became the head of her town panchayat but achieved poetic stardom. Her work became renowned, and was translated into many, many languages. And now the documentary that has travelled to tens of festivals – and with it Salma too – has catapulted her to world stage.

But has she achieved freedom in the real sense of the term? I wonder, because there is a scene in the film, where one of her grown-up sons, is upset that his mother does not wear the burka. He feels it is important for girls/women to wear that, because "men are easily aroused".

In spite of all this, Salma has no rancour or bitterness. She does not blame her family, which, she contends, had to live by the rules of its village. Otherwise, it could have been ostracised.

Are you a cricket buff? Participate in the HT Cricket Quiz daily and stand a chance to win an iPhone 15 & Boat Smartwatch. Click here to participate now.

Get more updates from Bollywood, Taylor Swift, Hollywood, Music and Web Series along with Latest Entertainment News at Hindustan Times.

Get more updates from Bollywood, Taylor Swift, Hollywood, Music and Web Series along with Latest Entertainment News at Hindustan Times.

Share this article