Women speak: #WeWillGoOut. Simply because we want to.

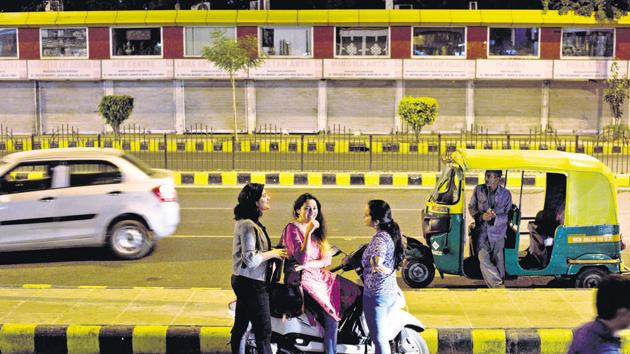

Young women are claiming their right to be out on the streets - day or night. Why can’t we?, they are demanding to know. But within these movements, issues of privilege, class and caste remain.

One Friday evening in February, Neha Singh and her friends went singing in Mumbai. At about 4 pm, they boarded the metro from Versova, and for the next couple of hours, Neha and the group had a good time playing antakshari. Their co-passengers, however, wondered why a bunch of young women and men were singing loudly inside a metro.

“In Mumbai, local trains have a culture of women singing; the woman have groups such as bhajan mandlis. But the metro is a different story,” says Neha. “People just enter. They don’t look at anyone. They are just indifferent and cold,” says the 34-year-old theatre actor and writer.

The point Neha is trying to make is this: if public transport was a bit more warm and inviting, wouldn’t a lot more women use it more frequently, without feeling scared? Wouldn’t safer public transport mean more women stepping out, going places, or just loitering around town?

A month before Neha and her co-passengers bonded over antakshari, Bengaluru-based Soumya Bhat, 23, and her friends had felt unsettled too. On a discussion over Facebook messenger, right after the city had witnessed an incident of mass molestation on New Year’s eve, young women such as Soumya had felt the need to step out and do something. Women’s groups had been outraging over the incident, and their anger had intensified after the disparaging remarks made by the state’s home minister attributing such incidents to the influence of “western culture”, and by implication, blaming the victims.

Soumya and her friends felt they had to oppose these “misogynistic comments”, and over the next two days, she and her friends tapped into their respective social media networks to plan an impromptu event. The plan for an ‘I will got out’ (IWGO) march, held on January 21, took shape. On the designated day, hundreds of women (and men) across 31 Indian cities stepped out to “reclaim public spaces” and assert their individual freedoms.

This was not an “angry” response, insists Soumya. The women were out to reinforce the idea that they could go wherever they wanted, whenever they wanted. They marched to counter the ideas and practices that limit their presence in public spaces — of ensuring that they are safe at all times, avoiding danger, dressing appropriately and the like.

Take back night

“Sexual harassment, especially on the street, is something every woman has faced. It’s become as common as breathing! People don’t realise, even staring at your cleavage is harassment,” says Japleen Pasricha, one of organisers of the IWGO in Delhi. At the event, participants such as Japleen recall how women stepped out to share their stories — of parents asking them to watch out, of constantly calculating a ‘safe’ time to head back, of mistrust in cops, and even, the pressure to “fight back” at all times. Instead, why can’t women just be?

This claim on public spaces and fight for individual freedoms is part of a specific genre of feminist activism to counter violence against women.One of the earliest such events took place in San Francisco in 1978, when thousands of American women marched with the slogan “take back the night” , as they agitated against rising violence against women. Back then in San Francisco, ‘take back the night’ was an anti-pornography march, and participants drew connections between violence against women and objectification of women’s bodies in pornographic images.

Read more: How sexist rules are stifling girls in BHU

From then on, generations of women, especially college students — both in and outside of the US — have used the slogan, “take back the night” , to reclaim public spaces, especially after dark, and discuss issues around street harassment and sexual violence in a safe space.

Back home too, there have been several such events, particularly in the aftermath of the December 16 gang-rape in Delhi. If the women’s movement of the 1970s and 1980s was concerned with issues such as dowry deaths and custodial rape, issues such as the right to public spaces and individual freedom has been one of the primary concerns for millennial women. “Issues such as dowry deaths concerned the post-Nehruvian generation. The demand for individual freedoms, sexual autonomy and such reflects the concerns of the post globalisation generation. Such movements involving middle class women also get more visibility, than say, the rape of a Dalit woman in Haryana. Also, issues stemming from an economic crisis such as the lack of good jobs don’t get talked about as much as violence does, ” says Professor Mary E John, senior fellow at the Centre for Women’s Development Studies in Delhi.

In 2013, for instance, a midnight march took place in Hyderabad; the following year, young women in Kolkata stepped out to “take back the night”, even as those in Mumbai joined the Why Loiter movement.

Inspired by a book by the same name, Why Loiter: Women and Risk on Mumbai Streets, women in Mumbai were asking a more provocative question: what if women set aside the discourse of danger and safety, and sought pleasure in just loitering around town? What if they were just hanging out, doing “timepass” over chai, or just watching the world go by?

So when Neha, founder of the Why Loiter movement decided to go to a public park with her roommate, the two realised that until now, most of their experiences in the city had been very limited. “We were mainly restricted to home, office, malls, restaurants and multiplexes, all of which are private spaces, but pose as public spaces. This was the first time that we were in a real public space, open and free for all. It was so much fun to just lie down on the grass, talk and stare at the sky,” she says.

Pictures of the event were shared on social media, and others started getting curious. Now, Neha and the group of women do this pretty much every weekend: their activities include loitering at midnight, cycling, playing board games in parks, drinking chai at roadside tapris. One of their events involves inviting men to come “dressed as women and loiter with us” to empathise with the idea that women get stared at all the time.

The movement to reclaim public spaces may have gained acceptance in the mainstream now, but it was not so until about a few years back. Hyderabad-based Tejaswini Madabhushi, 32, and Gitanjali Joshua, 27, recall how in 2012 — much before the outrage over the Delhi gang rape — they had been planning a “take back the night” event, but were “not confident of getting “even 50 people” together.

By January 2013, however, the idea of a midnight march had gained traction — about 3,000-4,000 people turned up for the event. After that, Tejaswini and a few like-minded women (part of the group, Hyderabad for Feminism) have organised similar events such as midnight marches and taboo trails — women go to places such as cheap bars and Irani cafes — in their city. One of the group’s popular events was the ‘mirror mob’ — a street performance where the men were shown as victims of harassment.

A class conundrum

Within these movements, many women say that they have had to battle with the questions of privilege, class and caste. What kind of women are occupying public spaces? Isn’t there an inherent urban bias? Doesn’t the politics of “reclaiming” come at the cost of positioning the lower class man as a potential ‘danger’ to the middle class woman?

“The issue of public spaces is being manifested as one of the most important issues for middle class women. For working class women, however, it might not be among the most important ones, even though it’s relevant for them too,” says Tejaswini. She recalls that once their events became popular, the group started getting called out for being “elitist”. Initially, the group was defensive, but later, they realised that despite other marginalised groups that were involved, it was always the middle class girls who would get media attention.

Both Tejaswini and Swarnima Bhattacharya (of IWGO, Delhi), however, feel that it’s difficult to dismiss these efforts as “biased”. While Tejaswini says that as middle class women, their presence in Irani cafes disrupted the status quo [of it being a men-only space], Swarnima feels that “urban” is a layered category. “Urban and rural are not black and white categories; ‘urban’ is also heterogeneous. For example, in Saket, there’s a polarised demography on either side of the street --Select City Walk on one side, and Khirki on the other,” says Swarnima.

Bhopal-based Kokila Bhattarcharya, a 23-year-old design student who participated in the IWGO march agrees, and explains why. In her city, no one talks about street harassment or sexual abuse, she says. “At least they got talking now.” The problem of women in public spaces is for everyone, says Kokila, while citing the example of women in certain urban and rural pockets, who are at risk of harassment each time they leave their homes to relieve themselves. “Imagine, would you take that risk just for going to shit?!”