The China challenge will shape India and the world

It always gets worse before it gets better. So, brace yourself for 2023 even while remaining cautiously optimistic.

When taking stock of everything that happened last year, one may be forgiven for thinking: 2023 cannot be worse than 2022. But history has a way of repeating itself and demonstrating the validity of the adage: It always gets worse before it gets better. So, brace yourself for 2023 even while remaining cautiously optimistic.

The Russia-Ukraine war was the “black swan” event of 2022 and succeeded in upending geopolitics and geoeconomics. 2023 may hopefully see the war peak and arrive at a stalemate if luck prevails. If that occurs, the economic repercussions of the war may begin to peter out by mid-2023. Does this mean an end to the war? Not necessarily. The chance of a low-intensity conflict continuing in the near term cannot be ruled out. With China doubling down on its partnership with Russia, the world may splinter into two blocs: One led by the United States (US)/West and the other led by China/Russia. Some countries will try and straddle both blocs. Europe has been woken out of its stupor by the war in Ukraine. While Europe will do its best in 2023 to cope with the fallout from the war, Ukraine will likely tie it down for the foreseeable future. “Ukraine fatigue” may rear its head and could strain intra-European ties. Europe’s arrival as an independent pole in a multipolar world will have to wait. Moreover, the European Union (EU)’s engagement and commitment to the Indo-Pacific may weaken due to the war in Ukraine.

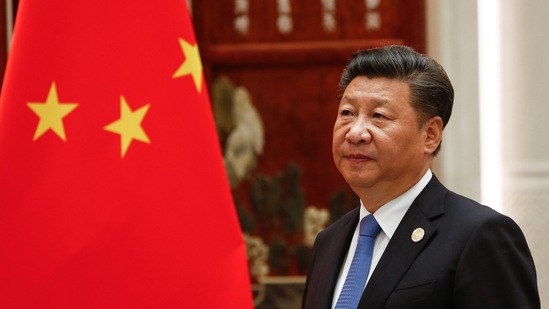

China begins 2023 by confronting a spate of internal and external problems. So, when 2022 saw the virtual coronation of President Xi Jinping as a modern-day emperor of China at the 20th Party Congress, everyone envied his consummate power. But a month is a long time in politics, even in China.

In the face of unprecedented protests, Xi had to do a volte-face and ease the stringent Covid-19 restrictions by December 2022, seeing his authority severely dented in the process. 2023 will arguably be the most challenging year for Xi. His priority will be to put his house in order. That may mean a non-belligerent foreign policy vis-à-vis the US (to gain time, if nothing else), but with other powers, expect China to be guided by ultranationalism and be both a wolf and a warrior.

The US, ironically enough, ended 2022 on a high. The economy recovered, though it was far from being robust. But it is the politics in America that gives hope for 2023. President Joe Biden looks surprisingly strong, former President Donald Trump looks surprisingly weak, and the society looks remarkably resilient. 2023 can only get better for the US. However, the external challenge to the US remains strong and emanates from Russia and China. The big geopolitical question for the US is whether it has the capacity and wherewithal to tackle Russia and China simultaneously. The test may arrive in 2023.

It is banal to say that the epicentre of geopolitics is the Indo-Pacific. In 2022, the war in Ukraine took centre stage, leaving the Indo-Pacific somewhat under the radar. This year may well see the US and some EU powers turn their attention to the Indo-Pacific, and the region may see increased contestation.

Japan is no longer a “defensive” power; the latest national defence and security strategy announces the arrival of Japan as a serious military power in Asia. But all eyes will be on China and what it does or does not do in the Indo-Pacific. Taiwan may not necessarily be on China’s agenda in 2023, but the South and East China sea will get its attention. North Korea may be capable of producing a “black swan” all by itself, drawing in South Korea and Japan in the process. Quad (the US, Japan, Australia and India) may well be tested in the Indo-Pacific in terms of whether it can deliver on its rhetoric. In sum, 2023 may see action and a reversion to the status quo ante in the Indo-Pacific after the war in Ukraine dominated the headlines in 2022.

For India, 2023 will be as challenging as 2022, if not more. Given the monumental development questions, the economy must get the required focus in 2023. But China will remain India’s principal security challenge, and the incident in the Tawang sector in Arunachal Pradesh may be a sign of things to come this year.

Engagement with China is necessary and unavoidable, but vigilance at the border will strain our resources. Can the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation summit in Delhi in mid-2023, chaired by India, be a moment for détente in Sino-Indian ties? Most importantly, the G20 presidency offers India an opportunity to leave its diplomatic mark in 2023. India will be the voice of the Global South and will focus on big issues such as the climate crisis, food security, and the Sustainable Development Goals. But can it also use its G20 presidency to make a difference in Ukraine’s conflict and contribute to world peace in 2023? Not by any means easy, but it’s worth a try.

Mohan Kumar is dean/professor, OP Jindal Global University

The views expressed are personal

Continue reading with HT Premium Subscription