In Nepal, where a battle for rights merges with geo-politics

HT travels across the Nepali Tarai, the hub of unrest and violence, to bring voices from a mass movement which has paralysed life, challenged the legitimacy of the new constitution, and led to a sharp dip in India-Nepal bilateral relations.

In two days, Binay Chaudhary lost both his father and his son. He was mourning as a child and grieving as a parent.

Chaudhary was sitting on a chair in his courtyard; the house overlooked a pokhari, pond, one of the many which punctuate the landscape across the plains. A lean man, he was bare-chested, in a dhoti, with his head shaved off. A janau, sacred thread, was hanging across his torso.

Chaudhary was quiet for a while, before narrating his story.

He was a caretaker at the Kathmandu Engineering College in the capital, where his uncle was on the board of directors. At about 3 pm on September 9, he got a call telling him Rohan, his 15 year-old son, had been shot. He did not believe it, but when his uncle began getting similar calls, Chaudhary took the first bus out of the valley. He reached Bardibas, a small bazaar on the east-west highway, in the middle of the night and came home to Jaleshwor, a southern district town right at the India-Nepal border, on a bike.

Rohan had been returning from his tuition in the afternoon. He was in the tenth grade and would have taken the School Leaving Certificate Exam this year.

A crowd of demonstrators had been protesting in the vicinity. The police was chasing them. Rohan was caught somewhere in the middle. When they used tear gas, he panicked and ran ahead. The police ran after him. Rohan, his father said, was now right in front of cops, and security personnel first shot him in the left foot, and then caught hold of him. “They then shot him in the chest.”

He was dead on the spot.

Two days later, as the family was yet to come to terms with the tragedy, Binay’s father – Ganesh – was out in the bazaar.

Ganesh was a journalist during the times of the royal autocracy, had headed the district chapter of the Red Cross and was a relatively well-known figure in the town. He was, however, not associated with any party.

He had a cup of tea in the nearby bazaar. Police vehicles, Binay claimed, had been firing bullets in the air and driving past the locality and the house we were sitting in. There was no curfew that day; there were no mass protests; and the state aggression was inexplicable to Binay. A policeman in plain clothes, on a bike, alerted Ganesh to flee to the side. Ganesh was on his cycle when the police jeeps found him. They shot him, in the head.

“See the cycle on the side,” Binay said, pointing to one in the open yard, “He was on it. It seems they targeted him, and I cannot understand why. He was not even active in the andolan(movement),” said Binay. He pulled out an old photo where his father was being honored by King Birendra, who was killed in the 2001 royal massacre, to show us what he looked like, to give a glimpse into his status.

The status had meant nothing at the end.

Binay was stoic as he finished.

Quest for dignity

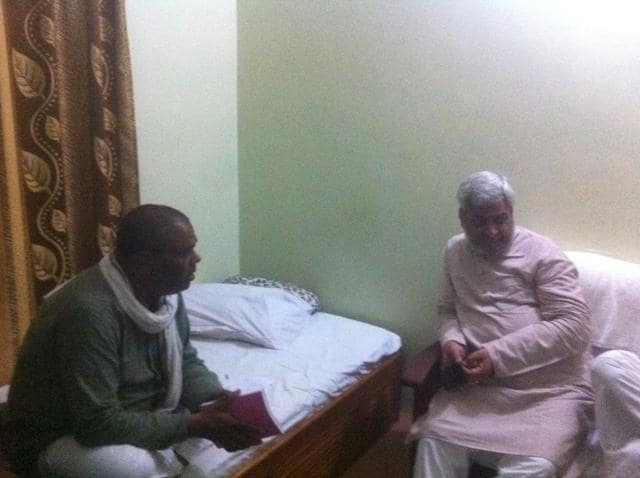

The previous day, I met Mahant Thakur in a small hotel room in Rajbiraj, a south-eastern border town.

Thakur is the chairman of the Tarai-Madhes Loktantrik Party. But his real importance comes from the respect he commands from across the political spectrum. A veteran Nepali Congress leader who was one of the closest aides of former PM Girija Prasad Koirala, Thakur switched to Tarai politics after the Madhes movement of 2007.

That movement forced the state to concede to the principle of federalism. Thakur then led a second agitation in 2008, which paved the way for an agreement that the Constituent Assembly would determine the nature of federal states, with an autonomous Madhes pradesh.

A short man, dressed in a kurta-pyjama, always measured and careful, even his fiercest critics have never questioned Thakur’s integrity or democratic commitment.

As we sat down, Thakur began by recalling incidents of the past 40 days – of how a man had been shot dead in Saptari district; of how peaceful protestors had been killed in Birgunj; of how police went inside homes, beat up people and called them ‘Biharis’ or ‘dhotis’.

During an evening rally, a group of protestors in Biratnagar had told HT, “They come into homes, ask for our citizenship, and tell us to go.” Go where, I asked. “Go to India.”

Madhesis had always felt deeply hurt about this tendency of the ‘hill establishment’ - which viewed them as somewhat lesser citizens, or outsiders, or Indian ‘stooges’ because of their kinship links and socio-cultural association with people across the border in Bihar and Uttar Pradesh.

The persistence of the labels seen as an affront to their dignity, coupled with the violations, had deepened Madhesi alienation.

The same tendency also seemed to have driven some of the constitutional provisions.

Right before Thakur set off for Rajbiraj last week, Prime Minister Sushil Koirala had come to see him. He asked- what did the Madhesis want?

Thakur had replied that the issues, by now, were familiar. “We asked him whether past agreements will be implemented or not. That is really at the heart of the issue.” These agreements revolved around issues of inclusion, representation and nature of federal demarcation.

On the ground, some are more informed than others; there are misperceptions about exact clauses; but at the core, a charter of demands around these themes have now widely become accepted.

The battle for representation

Nepal’s interim constitution specifically said constituencies would be created on the basis of population in the Tarai. The new constitution, however, says constituencies would be carved out on both population and geography.

Tarai’s forces feel this will result in a dip in representation - for the region is about 23% of the country’s geography and over 50% of the population. In the Constituent Assembly, out of 240 constituencies, 116 were in the Tarai. In the new legislature, out of 165 constituencies, Tarai wants a guarantee that 83 seats would be from the plains - the current formula which includes geography could see it dip to 60.

The sense that political representation would get reduced has got reinforced by two other provisions.

In the CA elections, almost 60% of the house was elected through the Proportional Representation model. Within PR, there were quotas for different excluded groups like Madhesis, Janjatis, Dalits and women. The new constitution shrinks the percentage of PR seats - in the absence of reserved seats under the first-past-the-post (FPTP) model, this dip will affect representation.

Additionally, in the upper house, the United States senate principle has been adopted, where each state sends an equal number of representatives.

Tarai leaders want the Indian example emulated, where states send representatives based on population to the Rajya Sabha so that citizens of the plains are represented in accordance with their demographic strength.

The issue of inclusion comes in the back drop of Madhesi and Tharu underrepresentation in state structures. Over 33% of the population, they constitute less than 7% in the Army; out of 75 Chief District Officers, only two are Madhesis and this is indicative of the domination of the hill upper castes in the upper echelons of the bureaucracy.

Tula Narayan Sah, a prominent Madhesi analyst and activist, says, “What matters in a state is its coercive apparatus and its financial apparatus - who controls the paisa, money, and the banduk, gun? We are neither represented in the security forces, nor in key decision-making structures in the bureaucracy which deal with state finances.”

To remedy this situation, the interim constitution stipulated there would be proportional inclusion in state organs of excluded groups. The new constitution drops the term ‘proportional’ and adds a range of other groups, including the traditionally dominant hill upper castes, farmers, workers, youth.

The architecture of affirmative action, Tarai leaders say, is thus deeply compromised.

Search for equal citizenship

My grandfather studied medicine in the North Bihar town of Darbangha and migrated to Nepal over 65 years ago. He soon became a Nepali citizen, joined the government’s medical services in Rajbiraj where I met Thakur last week, resigned to set up a business firm, and dabbled in right-wing politics indirectly. My father was born a Nepali, studied partly in Kathmandu and partly in India and made his life in Nepal as a professional consultant.

We are Madhesis.

But while my grandfather was a migrant and thus a person of Indian origin, many Madhesis have always lived in what is the Tarai. They became Nepalis because of arbitrary state demarcation after the Anglo-Nepal war of 1814-16.

33 years ago, my parents got married. It was another instance of the cross border marriages that take place between people in the Nepali plains with those across the border.

My mother was born and brought up in then-unified Bihar. She made Kathmandu her home, taught in a school, trained herself in the field of promoting gender equality and social inclusion, and worked extensively in the development sector for over two decades.

And yes, she became a Nepali citizen.

Once the constitution was promulgated, she sent an email to a group of friends. “I am so, so disappointed by the new constitution and feel so pained.”

“I, even after spending a major part of my productive life in Nepal as a Nepali citizen, after working so hard for the rights of women and the excluded, after travelling to so many districts and remote areas of Nepal, I cannot hold any official position.” She ended with saying she felt disenfranchised. “It is a very painful feeling - as if I am a lesser citizen than others.....as if it is not my country after all.”

The new constitution, for the first time in Nepal, has created categories of citizenship where some are more equal than others. Those who are naturalised citizens are ineligible to hold a range of public positions - from the president to the prime minister to chief ministers to heads of judiciary and security organs.

My mother has no political ambitions and other countries too have special provisions for naturalised citizens. But in this case, the principle involved triggered a backlash. It appeared targeted at Madhesis because of the extent of cross border marriages in the plains. It appeared to be driven by the fear that Indians would otherwise marry into Nepal and take over the country’s politics and government. The provision generated a perception across the plains and bordering districts of Bihar that the ‘roti beti relationship’ was now under threat.

A similar ‘nationalist’ fear was used to justify what is now universally-recognised as a deeply discriminatory provision. Nepali women married to foreign men cannot pass on citizenship by descent to their children; a similar clause does not exist in the case of Nepali men married to foreign women.

A young economist, Apoorva Lal, has written the clause will cause widespread statelessness and gives a hypothetical example of a woman from the Nepali Tarai district of Mahottari marrying a man from Bihar’s Madhubani district. Their child is barred from citizenship by descent because of the ‘abhorrent law’, and must apply for naturalised citizenship which places her at the ‘demonstrably racist whims of the bureaucracy’.

There is a high chance such a child would be denied citizenship, and left stateless, and thus deprived of opportunities to sit her for school exams, purchase land, open a bank account, vote, get a passport and avail other services, argues Lal.

Nepal’s best known English writer, Manjushree Thapa, wrote a deeply moving, almost heart-breaking, piece after the constitution was promulgated.

Manju is a close friend. Her commitment to Nepal, its suffering, its democratic movements, is deep. When her father was the foreign minister under a royal dispensation, she was on the streets and even received blows by state forces.

She has done more to put Nepal on the international literary map and bring alive its own local writing to a broader audience through translations than any other writer around. She retained her Nepali citizenship despite living in US and Canada for half her life.

But something in her died when she saw patriarchy institutionalised. “Mann ni maryo,” she wrote.

She burnt the constitution.

As the respected commentator, Pratap Bhanu Mehta, wrote in The Indian Express about Nepal, “Rather than assert its autonomy, it has let the ghost of India rule; it shall short-change its own women to keep notions of purity of descent alive.”

Some Madhesi leaders are often tempted to seek immediate citizenship for foreign wives of Nepali women (their bahus) but not for foreign spouses of Nepali women. And here, they clash with the feminist movement which seeks equality between the two.

Both sets of foreign spouses must be granted citizenship within an equal time period. The current constitution leaves this ambiguous, to be determined by law.

Given the same mindset - prioritising hill men, deeply suspicious of India and those with past, current and even future links to India - drives citizenship provisions targeted at both Madhesis and women, activists believe the movements must remain allies.

The imagined homeland

The mood was cheerful yet aggressive at the Janak chowk in Janakpur. The town lies at the heart of imagined Madhes territory.

Every evening for over 45 days, a crowd gathered around the crossing to register its protest. Last Thursday, a Madhesi youth group, an association of professionals and an intellectual collective had together organised a mass meeting.

As people kept swarming in, the excitement grew. Every few minutes, someone would give the cry, Jai Madhes, and the crowd would echo the slogan. Madhes Sarkar was painted in bold on the gate of a government building on the street corner.

The Madhes sarkar slogan had picked up for the first time in 2007, when the demand for federalism got articulated through a mass movement. At that point, the chant was for ‘ek Madhes, ek pradesh’, one Madhes state across the plains from the east to west. This claim however found few serious backers beyond the core Madhesi territory in eastern Tarai, for it would defeat the very purpose of having federalism. It ignored the heterogeneity within the plains, and Tharus in particular objected and sought a province where they were demographically dominant in the western plains.

By early 2012, Madhesi and Tharu groups had come to a broad settlement – the area from Jhapa in the east to Parsa in central-eastern Tarai would be the Madhes province, while the region from Nawalparasi to Kanchanpur in the western plains would be a Tharuhat province.

The older parties, however, were reluctant federalists. When they came around to the idea, due to the force of the movements for identity and rights, they insisted on carving out provinces vertically instead of horizontally, from the north to the south, to include the Himal, mid-hills, and the plains.

Madhesi parties saw this as unacceptable – for they saw it as a conspiracy to divide the Madhesi identity, dilute their demographic strength, and feared that in such provinces, the hill upper caste communities would continue to dominate the politics.

The problem was particularly acute in the case of five districts – Jhapa, Morang, and Sunsari in the eastern plains and Kanchanpur and Kailali in the western plains – since it had got tied to the personal interests of top leaders.

UML chairperson, K P Oli, and Nepali Congress’ influential leader Krishna Prasad Sitaula are from Jhapa and insisted the eastern belt must be merged with the hills; former Nepali Congress PM Sher Bahadur Deuba, was from the far west hills and insisted that Kailali and Kanchanpur must be merged with a united far west province rather than with the plains.

The new constitution catered to the interests of these leaders.

Additionally, six hill districts were added to the centre west province. Tharus would thus be reduced to a political minority within the western province they had hoped to dominate. Out of 20 Tarai districts, Madhesis would have to settle for only eight districts which would constitute a plains-only province.

The Madhesi and Tharu Street reacted with fury.

Sadbhavana Party chairman Rajendra Mahato is a rather aggressive and vocal leader. He has been a minister in several governments. We met in the same Rajbiraj hotel, where all leaders had convened.

“The mood is this is an aar ki paar ki ladai, a decisive battle. This is the third time Madhesis are fighting for the same issues in less than ten years. People tell us, take another 15 days but get us justice this time.” The bottom-line, he said, were two provinces in the plains.

Privately, other Madhesi leaders are open to a compromise formula – where Jhapa and Kanchanpur are left with the hills, and Morang, Sunsari and Kailali are divided with parts of the districts merged with the plains.

Bijay Jhunjhunwala owns Hotel Welcome in Janakpur. I used to stay there during my initial reporting trips to the region back in 2007. The first Madhes movement had just taken place, forcing Kathmandu to accept the idea of federalism in principle. There was a proliferation of armed groups, where the distinction between politics and crime had blurred. Bandhs were frequent and there was fear. Jhunjhunwala used to tell me how the movement had got diverted from its goals, how his business was suffering and how all they wanted was peace.

The hotel had now been renovated and upgraded. But that was not the only change.

As we sat in his hotel lobby, Jhunjhunwala said this movement would unite the nation once the demands were addressed. “This is a jana andolan, mass movement. It is peaceful and there is nothing artificial about it. This will help unite us on equal terms. There will have to be a political settlement.” He rejected the contention that since most Members of the Constituent Assembly had approved the constitution, protests had little legitimacy. “Representatives matter as long as voters are not on the streets. Once voters are out, their voices have to be heard.”

The hotel had seen a drastic dip in occupancy. From an average of 50% occupancy, it was now almost empty. Janakpur was a tourist spot for Indian pilgrims keen on darshan of the Janaki mandir - where Lord Ram and Sita wed according to Ramayana- as well as a centre for those who sought to understand Mithila civilisation. There were at least 200 hotels in the town, and all had suffered during the strike.

“These hotels employ at least 3,000 people. Then there are daily wage laborers. Everyone has lost financially. But this is a necessary movement. We should not call it off till demands are met. It will lead to progress,” said Jhunjhunwala.

Every businessman and shopkeeper, usually the constituency most unhappy with political unrest, I met in Janakpur echoed Jhunjhunwala.

The movement was not restricted to any class or social group.

As I got down at the Biratnagar airport, Govind took me in his rickshaw to a friend’s place. When I asked him about the reasons for the protests, Govind said, “We don’t accept this constitution. It does not give a Madhes pradesh.” But the constitution did give a Madhes pradesh, I insisted. He replied Biratnagar must be included in it.

Biratnagar is one of the Tarai’s biggest towns. It is also demographically mixed, with an almost equal proportion of Madhesis and people of hill-origin, Pahadis. The hometown of the Koirala family, Biratnagar is often seen as the political hub of the country, the centre of democratic politics.

Shekhar Koirala represents Biratnagar in the parliament. He is a medical doctor who made a late switch to politics, and was a key figure during the early years of the peace process with the Maoists. Koirala’s uncles, BP, GP and Matrika, have all been Prime Ministers.

Koirala told HT his constituency includes about 55% Madhesis and Tharus, and about 45% pahadis.

“Biratnagar residents have had to suffer because of the bandh. But Madhesis and Tharus are struggling for their identity. Kathmandu has not been able to understand the situation.” He said he had spoken to the district administrators and police officials to ensure there was no brutality against his constituents.

Koirala was worried about the implications of the strife.

“No caste is dominant in any place in Nepal. So there is a high chance of an ethnic conflict. It is important that there is a settlement at the earliest.” Recalling the legacy of his own family, Koirala said that they had always been committed to maintaining the social fabric of the town. “We must accept the identity of Madhesis and Tharus.”

He has suggested the formation of a commission, with experts and not party-nominated individuals, with the mandate to suggest revisions in boundaries within a month. Mahato however rejected the idea of a commission and said only a final federal settlement would be accepted.

A state crackdown

Mahant Thakur attributed the surge in the movement to these grievances, aggravated by state brutality.

“As oppression increased, people began coming from the villages. We never called them. But they arrived in thousands. This has become a mass movement now.”

Thakur said he had told Koirala the government was inserting poison in society.

“I told him the first thing is to stop violence. Terrorism and communalism is poison, people don’t usually forget this easily. And what is happening is state terror.” Thakur pointed out to the PM that the security forces can enter one village, but other villages will rise up and get mobilised. “Unke paas banduk hai, tu janata ke paas sankhya hai. They have the guns, but people have the numbers.”

This had resulted in a situation where anger levels had shot up in villages, police posts had been displaced, and the state had retreated. Civil administration was non-functional, judicial officers had fled, and if the state was present, it was only in its security avatar.

The violence had not only come from the state. In August, in the western Tarai district of Kailali, Tharu protestors had killed eight police officials. In Mahottari, Binay Chaudhary’s home district, an injured police official on his way to a hospital for further treatment, had been brutally killed.

Surendra Shrestha was a local police official in Biratnagar. We met close to a protest rally in the evening.

Shrestha was in a police van, driving slowly, keeping a distance from the site of mass demonstrations. “As soon as they see us, they start pelting stones and hitting us. Look at my van. The window pane was broken early in the strike. This is not a peaceful protest.” I asked him about complaints from the protestors police had entered their homes, asked for citizenship papers, and harassed them. Shrestha said he did not know anything about it.

Human rights groups have noted the violence but said the state response had been disproportionate.

Dipendra Jha was, until recently, the chairperson of the Tarai Human Rights Defenders Alliance, which has a network of activists and volunteers on the ground. THRD is the only national human rights group which has done on-the-ground documentation of excesses. As we drove across the deserted East West Highway, he explained the human rights situation.

“The violations have been systematic. The state’s intention does not seem to be crowd control or dispersal of masses, but to kill. We have seen bullets above the waist, either in the head or chest. Two people have been shot in the back – Rajeshwar Thakur in Gaur and Dilip Chaurasia in Birgunj.”

There had been indiscriminate firing, which had killed even Pahadis. “In a bazaar very close to the border in western Tarai, protestors had pelted stones at the police. Agitators had run away, and security forces began shooting from a bridge. There was a market close-by. And five people were killed. This included a four year old child, and even two Pahadis.”

Jha makes an even more serious allegation – that the state had tried to communalise the unrest, when policemen in plain-clothes had entered into scuffles with Madhesis. “We have a video which shows one section taking orders from the local police officials. Security forces have also used communal terminology.”

Jha had filed a writ in the Supreme Court, which had issued a state order against excessive use of force. The National Human Rights Commission, Amnesty International, the UN Office of High Commissioner for Human Rights have all issued statements condemning state action. And Upendra Yadav, chairperson of a major Madhesi party, goes as far as to call it ‘genocide’ - a term most independent activists disagree with.

All of this had fueled a new Madhesi narrative. Real fears have got reinforced; exaggerations are common and misperceptions crowd any conversation. But the sentiment is now overwhelming.

Their demands were not accommodated; the constitution was rammed through even though political forces of the region - who may be numerically diminished but speak for the rights of the residents of the region - remained out of the process; Kathmandu behaved differently with them than with the hills where grievances in some pockets were immediately heard to revise boundaries; and instead of recognising it as an underlying political issue, state resorted to force and many became ‘martyrs’. The struggle was ‘just’ and could not be given up.

From across the border

In one corner of the Janak Chowk, the Yuva Vyapari Sangarsh Samiti, Young Traders Struggle Committee, had put up effigies of national leaders with price tags, signaling they had all sold out. A model of Prachanda, the Maoist chairman, was sitting right in the middle, on a cycle.

I asked two protestors why they had gifted the leader a cycle, “Prachanda had said that if India does not allow oil to come in, he would ride a bicycle. We want to tell him that even the bicycle is Indian and gift one to him.”

Everyone laughed.

Soon after the constitution was promulgated, India ‘noted’ the development but did not welcome the text. This came in the backdrop of repeated Indian statements and appeals to Nepali leadership to ensure the ‘widest possible agreement’ and draw out a constitution which was owned by all regions of Nepal, and all sections of society.

Prime Minister Narendra Modi even sent a special envoy, Foreign Secretary S Jaishankar, to Kathmandu with a firm message that India would not be able to welcome a constitution when half the country was under curfew, when army was deployed, and no Tarai force was a part of the constitutional settlement. Many felt his visit was too little, too late, and the message went unheard.

A day after the promulgation, India hinted at the disruption of supplies across the border, pointing to concerns of transporters who were insecure at the developments and protests on the Nepali side. The Kathmandu media reported it as the coming of an ‘unofficial blockade’, which is when Prachanda said that he would rather ride a bicycle than give up ‘self-respect’.

Janakpur’s young traders were not too impressed clearly. Even as many in Kathmandu slammed the Indian position, people across the Tarai and the bordering districts of Bihar welcomed it.

I travelled to three border posts last week to get a sense of the ground dynamics.

The Birtamod-Sursand border is a symbol of what makes the India-Nepal relationship so special, so unique. There is no fence, people cycle and walk across, a barren strip is what divides the two countries, and few would find it easy to discern when they have left one country to enter another. A few buses were lined up on the Indian side and a security official told me no cars had moved. He attributed the disruption to protests.

Sunil Rohit of the Sadbhavana Party was supervising the erection of a temporary structure on the Nepal side. He told HT they planned to stop any movement from the border.

“But if your battle is with Kathmandu, why are you disrupting supplies here?” I asked. Rohit said they realised on a short visit to the capital that while the Tarai had been reeling from a bandh for over 40 days and people were suffering, there was no impact in Kathmandu, where people were going about their lives like nothing had happened. “We have decided to block the supplies because until Kathmandu is affected, they will not address our demands.”

The Birgunj-Raxaul crossing is the busiest intersection on the Nepal-India border.

On the bridge that marks No Man’s land, Madhesi protestors had congregated in hundreds when I met them late on Saturday evening. Indian citizens and civil society groups from Raxaul across the border organised one big meal, a light snack and tea for the protestors every day - the sympathy was apparent because of shared kinship and cultural links and a strong sense that Madhesis had been dealt with unfairly. Supplies had got disrupted here too, and there was a queue of trucks for as far as 20 kilometre into the Indian side.

The government in Kathmandu has called it an ‘unofficial blockade’ by India, and begun international lobbying against the move. The Indian position is that it is not them, but the internal protests within Nepal which have disrupted supplies. And the sooner a political solution is found within, the sooner the border situation would get resolved.

The truth appears to have many elements.

Tarai protestors have blocked the border, disrupting movement, and the Nepal government has done little to resolve the issue. The Indian side has tightened security and customs formalities, and is in non-cooperation mode - if it went out of its way to enable movement till last week, it has now turned indifferent or even cold. The transporters are worried and rumours swirl around in bordering towns about the possible attacks that may come their way if they crossed in.

After eight years of covering the twists and turns of the Madhesi movement in Nepal, what was striking during this visit was the depth of alienation and the increased radicalism on the Tarai street. Rarely has the question that lies at the heart of it assumed such importance - what would be the relationship between Nepal’s capital and its southern periphery; what would be the shape of Nepal’s new inclusive political order; and will its various communities be able to bridge the trust deficit?

The answers will determine the future of the Kathmandu-Tarai-Delhi relationship.