Excerpt: Regrets, None by Dolly Thakore

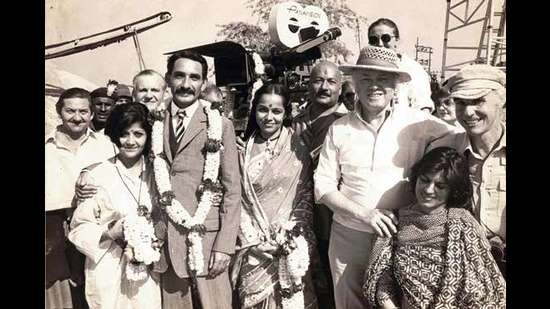

Veteran theatre personality Dolly Thakore’s memoir is honest about her life and its share of glamour, love and heartbreak. This excerpt from Regrets, None is about her experience as the casting director for Richard Attenborough’s Oscar-winning film, Gandhi

In July 1979, Rani Dube passed through Bombay. She’d brought Richard Attenborough with her. Richard’s long-cherished dream project, Gandhi, was close to realization. Rani was the co-producer, and she had brokered a meeting between Richard and Indira Gandhi. Mrs Gandhi had given the project her blessing and introduced the two of them to the National Film Development Corporation of India (NFDC)…

On the 25th of July, Rani brought Richard over to my apartment at around 3 in the afternoon. I was breastfeeding Quasar. We chatted for a while. The walls of our home, as ever, were covered with photographs from plays Alyque had directed. Talk turned to the theatre, to the BBC, to children and life. At half five, I rang Alyque to say, “Ahem, Richard Attenborough is here, and would you come home and we can all have dinner, because, you know, Richard Attenborough?”

I remember we went to Copper Chimney and had Kakori kebabs. But the moment Alyque walked in through the door, Richard turned to me and said, “That’s my Jinnah.”

Two days later, he rang me up.

“Dolly, it’s Richard,” he began. “We’re starting work on Gandhi, as you know. And I was wondering if you’d like to be the casting director?”

It was on the strength of the photographs and the long chat we had that day, about my years in the theatre and my work as a model coordinator and as a host. But mostly, I suspect, it was just a hunch.

I jumped at it. Although no one I knew really knew what ‘casting’ entailed. So, it was just like every other job I ever had.

By November of 1979, Quasar and I moved to the Ashoka Hotel in Delhi. We lived there for the next six months. I was casting director for Gandhi, but I was also the unit publicist and PR liaison.

Richard had already decided on his Gandhi: Ben Kingsley. He was going to cast all the white parts from Britain (and in the case of Martin Sheen and Candice Bergen, the US). I had to find all the Indian actors.

I also worked as a theatre critic at the time, and I watched almost every play on the boards, across the city. I spotted Rohini Hattangadi and called Richard in Delhi.

“There’s a young actress I want you to see,” I said.

“Kasturba?” he asked.

“Kasturba,” I agreed.

Richard was leaving Delhi for London that night. But he would stop in Bombay if he could meet this actress. Would I be able to take a room at the Airport Centaur? He’d nip out, see her and then go back across the street for his flight to London. International flights operated from the same terminal.

Rohini had a show that night. It was past 11.30 before she made it to the Centaur. Richard and I were sitting on the couch, and the moment Rohini walked in through the door, he clutched my thigh.

“This is it, Doll!” he whispered.

Richard had seen something intangible – a quality, an essence. He had a hunch about Rohini. She’d fit into his vision and further it. He could see her on screen. That was what casting was about. That was what one half of filmmaking was.

…”If she can lose about eleven kilos, that’s my Kasturba.”

This, then, was the other half of filmmaking: the journey from casting to the shoot. I rang Rohini the next day. Together, we went to see a Dr Vishnu Khakkar at Kemp’s Corner. He was a dietician…He examined Rohini, heard the brief and then told her that she could eat two chapattis and a bowl of dal for lunch and dinner, and nothing in between. And she had to walk for an hour and a half every day.

Rohini lived in Wadala at the time. Right or wrong, I was convinced that she might follow the dal-roti diet but, left to her own devices, there was no way she was going to take a walk every day. So she’d come to mine, we’d go to Vishnu’s office and lock ourselves into the second room. I’d sit in the chair and she’d walk around the table for an hour and a half. We did this every day for three weeks. She lost five kilos, and I called Richard with a progress report.

“Send her,” he said.

The delegation to London comprised Rohini, Smita Patil, Bhakti Barve and Naseeruddin Shah.

Smita Patil was very much the trendy pick. She was quite a big star by then. She was critically acclaimed and shared, in particular, a wonderful creative relationship with Shyam Benegal. But she wasn’t right for the role. She was too sultry, too aware, had too much spark for that version of that story. It would’ve been bad casting.

My pick – so much water under the bridge now – was actually Bhakti Barve. She was a fine actress. And I felt that she looked like Kasturba. That was enough to seal the deal in my mind.

Naseer’s trip was a political move. He’d made it clear that he was only interested in playing Gandhi. And Richard was set on Ben. But Naseer was a star, a name in the Bombay film industry, and Richard wanted to pitch a host of other parts to him – Nehru, in particular. Which shows how well he knew Naseer. Because that was never going to happen.

Money wasn’t a problem. We put this group of actors on a flight to London to shoot some tests. In fact Gandhi, as my first film, was a bit of a ruinous experience. The producers allowed – “empowered”, I think, is the right word – me to take decisions and paid for them without asking any questions. In other words, they trusted me to do the job they’d hired me to do. They delegated and left it at that; if I screwed up, that was completely my responsibility. No other job has come close.

Richard said ‘no’ to Naseer playing Gandhi. Naseer, in turn, said ‘no’ to Nehru. He wasn’t part of the film which – to this day – feels odd, given that I cast 498 Indian actors. A lot of people remember him being in the film! They’ve ghosted him in, because it feels logical that he would’ve been there. Naseer would have to wait about two decades to play Gandhi in Feroze Khan’s stage production.

Richard called from London to say that Rohini was his Kasturba. He loved her simplicity and naivety – things that are difficult to fake on screen.

The next step was to better her English. I got Kusum Haider to be her teacher in Delhi. I suppose that would be her ‘dialect coach’ in this day and age. Rohini was a model pupil. She maintained her diet and her exercise routine, and she was serious about her English lessons and the spinning class she took with Ben.

Wait. What I mean is that both Rohini and Ben learnt how to weave cotton. They weren’t on exercise bikes, peddling madly.

One of the major criticisms at the time was that Ben Kingsley was too ‘muscular’ to play Gandhi. Ben did all he could to remedy that. He was on a strict diet, and he did a lot of yoga. When he arrived in India, we removed all the furniture from his hotel room so he had to sit and sleep on the floor. The walls were covered with pictures of the Mahatma.

The backlash to the casting decision was inevitable. We were always going to have to confront the question: How could a foreigner play Gandhi? Bizarrely, the makers of ‘parallel cinema’ were the only ones who raised the issue. They showed up on the first day of shoot, waving black flags. I spotted my friend Shama Zaidi amongst the picketers. On our side of the fence was Govind Nihalani, one of the leading lights of the parallel movement but also our second unit cameraman. The protests were orderly. No one ran around breaking things; there were a number of write-ups and opinion pieces. Richard was polite, but firm – Ben Kingsley was his Gandhi. All said and done, Ben was of Indian stock. His grandfather had migrated from India. I mean, we were really straining the boundaries of credibility with his Indian ancestry, and everyone knew it. But we had Mrs Gandhi’s backing. Doors opened for us, trains ran on time and locations were a cinch. Gandhiji’s contemporaries, Ramkrishna Bajaj and Bharat Ram, were closely involved. The NFDC had given us nine crores.

The protests made it to the newspapers and were duly praised; the film rumbled on.

At the pre-shoot party for the Indo-British unit, Roy Button turned to Kamal Swaroop, both third ADs, and asked for a glass of water. Kamal replied, “The Raj went a long time ago.” That was about it for on-set strife.

Would we get to make it the same way again? Today? With a British director and a British lead? I don’t know. That’s dinnertime conversation. Would they get to make Apocalypse Now the same way?

We rolled on the 26th of November 1979. And it really was an army on the move. It had taken Richard decades to get to that moment, and you could see how much it meant to him, because every single minute on that production had been accounted for. People knew exactly what they were supposed to be doing.

Amal and Nissar Allana worked as set decorators. Their universe ranged from trains to cars to jewellery, costumes, shoes. Every detail had a separate team, and all roads led back to Richard – casting meetings, production meetings, lighting meetings, script meetings. And somewhere within that maelstrom, Richard found time to concentrate on the performances, to create a work of great integrity and beauty that has stood the test of time.

We shot in Porbandar, Bombay, Pune. Never Ahmedabad. The scenes set in South Africa were shot in Okhla. The shot of Gandhi silently giving a poor woman his safa by letting it drift across to her in the river was shot in Udaipur.

…In a strange way, I became the doorkeeper for the production. The outside world had to get through me before they got to the film, for anything. The requests ranged from the routine to the ridiculous. Everyone wanted a slice of the pie: producers, hangers-on, friends, politicians. People wanted to visit the set. People wanted to meet the actors. People wanted a say on the screenplay.

We were lucky that Richard had been dealing directly with Mrs Gandhi. That meant we could be firm. Sometimes, we just had to buy peace. Ben occasionally wanted a beer at the end of a day’s work, and we had to ensure he wasn’t seen by the press. We’d already had one headline: ‘Ben Kingsley, Gandhi, drinking beer.’ He was also an attractive man in the middle of a career-defining performance, so we had to shield him from the ladies. If he did stop to speak to someone, the press couldn’t get wind of it. For a while, I was his minder in the modern sense – the advance party, the bodyguard, the person pulling strings, just out of shot.

It was an exhilarating time, but it was bloody hard work. Luckily, Richard and I had found our wavelength early with Kasturba, and I had a strong sense of what he was looking for.

My old friend Roshan Seth played Nehru. We’d tested Victor Banerjee as well but Roshan had the sophistication of Nehru and won hands down.

…

Richard cast Saeed Jaffrey as Sardar Patel. I didn’t agree with that call. I still don’t. He just wasn’t right for the role. Harsh Nayyar played Godse. He was another Indian actor from the West (America or England, I forget) who wrote to Richard and won the part.

I had a hand in everything else. From Supriya Pathak to Neena Gupta, and Om Puri (God rest his soul, that brilliant, brilliant man) to Shekhar Chatterjee, who played Suhrawardy and whom I’d spotted in Calcutta. I mostly cast actors from the theatre. I mentioned Bhanu Athaiya to Richard, and she went on to win the Academy Award for costume design. She was a very well-established designer before Gandhi. What I loved, though, was her mumbled complaint at one point, “All I’m making is kurta pyjamas.” But then, that’s all the Congress leaders wore at that time, with the sole exception of Jinnah, who had some rather excellent suits. Alyque was hopeful that he’d get to keep his clothes from the shoot and was most disappointed when they were on the next flight to England.

Of course, when Bhanu won the Oscar, it was all “… yes, Jodhpuri pyjamas but, you know, I had to cut them in a very specific way.” Ah, show-business.

…The Indian premier was at Regal. I can confirm that Indira Gandhi did not, in fact, attend. At the time, I thought it the most exhilarating moment of my life, the crowning glory. With the passage of years, I’ve gained a little perspective. But that film taught me so much and gave me a set of memories I’ll never forget, some of them the proudest of my career. …And that funeral scene – one of the greatest ever filmed.

It went to the Oscars and won so many awards. But, by then, it was a British film, Richard’s film, and seemed very far away indeed.

Richard and I remained friends until his death in 2014. Ben Kingsley visited India again in 1990, and I had everyone over for a meal at my house. It was lovely. He’s now a Knight of the Realm. And I hear he prefers to be called ‘Sir Ben’.

I’m glad I was there; I’m glad I was part of it.