Una, Gujarat’s centre of Dalit protests, fears backlash for its resistance

It is around 10 pm and at least 200 men, women and children, crowd the 20 feet between the taxi and me. The air smells of sweat and Mawa (chewing tobacco). Some of the older men are saying something to Piyush about me in Gujarati.

“They think you are a CID agent pretending to be a reporter,” says Piyush Sarvaiya.

It is around 10 pm and at least 200 men, women and children, crowd the 20 feet between the taxi and me. The air smells of sweat and Mawa (chewing tobacco). Some of the older men are saying something to Piyush about me in Gujarati.

“Because you slept in the village for a few nights. You tuck your shirt in, wear shoes and speak in English to somebody in Delhi.”

But that’s my editor, I try to explain.

“I believe you, they don’t. There are rumors about undercover police agents and BJP spies keeping an eye on our family,” Piyush says.

Behind the suspicion and the stares is tale of resistance to caste oppression in this village in western Gujarat, where the Sarvaiyas settled 200 years ago.

They were pitchforked to the national limelight last month after four Dalit men were flogged by alleged cow-protection vigilantes in Una, sparking nationwide protests.

The anti-caste protests – and a march from Ahmedabad to Una – have been widely hailed as an important moment in India’s fight against caste.

But for the families of the victims, the resistance is mixed with fear of an impending backlash from dominant castes and a growing feeling that that they are being watched.

Clan members, who had dispersed across Saurashtra over generations, are now hurriedly rebuilding forgotten relationships and going into a huddle.

Their fears came true on Monday when groups of Dalits were attacked by dominant-caste mobs on their way from a mega gathering at Una.

The Dalits say their demands for a dignified life, a refusal to do menial jobs such as skinning dead cows and demand for five acres of land has infuriated their erstwhile masters.

Him and others have gathered to stand by his cousin Balubhai, who – along with his sons and nephews -- was thrashed by the cow protectors in Una on July 11.

“Every second Sarvaiya you see here must have faced some abuse or attack from the Go-Rakshaks or some upper-caste mob in the last ten years. Balubhai is not the only one,” Piyush says softly, next to a sobbing Balubhai.

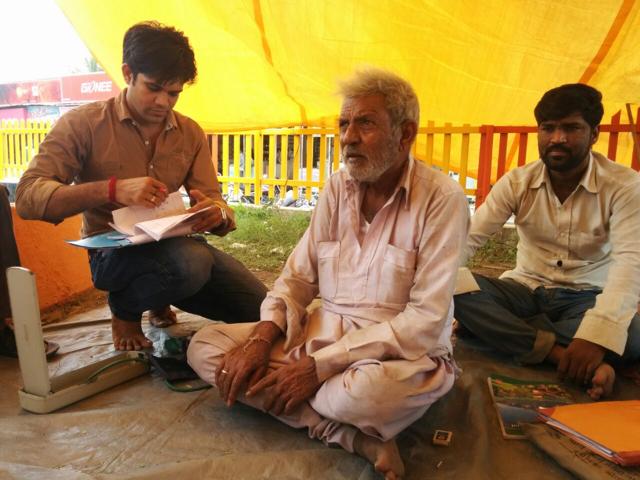

Piyush and others have decided to go on a hunger strike to press for their demands. One of the leaders of the protests, Jignesh Mevani, has threatened fresh protests and a rail blockade if the demands aren’t met in a month.

Dalit Pride

They may be fearful but the Sarvaiyas don’t follow the mainstream imagination of Dalit atrocity victims as meek and defeated, struggling to feed and clothe their families.

The Sarvaiyas might not be as rich as the Patels yet but they are on their way up the economic ladder, a progress they say has met with hostility from their erstwhile masters.

There was a time when Dalits here were not allowed to wear the magnificent white turbans you see in Gujarat tourism brochures. In the Sarvaiya gathering, there are people like Anhivad Amirbapa Sarvaiya (90) who wears not only the turban but also twirls-up his mustache and carries a walking stick with a shiny brass knob like a Patel landlord. His clothes are spotless as he no longer needs to work as an agricultural labourer. His son is now in the Border Security Force.

There’s also Jeetu Sarvaiya (22), the first Dalit boy in Mota Samadhiyala to study in an engineering college. He’s got a cropped footballer hairstyle, wears a nicely fitted T-shirt and goes to the college gym.

He confesses to receiving many proposals every Valentine’s day - some even from upper caste girls who, he says, mistake him for a Rajput. His cousin Arvind Sarvaiya, who hasn’t gone beyond the eighth standard and still lives in Mota Samadhiyala, is a digital native. He is comfortable with Facebook, WhatsApp, Xender and Instagram. He understands how twitter works but doesn’t get the point of it yet. He also follows Gujarati news websites on his phone such as Divya Bhaskar, which he says was the first to report on the Una atrocity.

Piyush says the growing prosperity of the Sarvaiya clan is making the upper castes jealous and violent. But there are others in the clan who believe ‘Sarvaiya’ became a marked name because of Piyush’s family and his anti-caste activism.

“I was there that day,” Piyush says of the July 11 tragedy. He saw around 500 men crowding around four chained boys, and taking turns to whip them with a slat outside the Una courthouse. He didn’t look long enough to recognize the boys but he instantly figured out who the men leading the assault were -- cow protectors from the Koli, Darbar and Patel castes. The victims, he guessed, were Dalit or Muslim.

He didn’t look because he had other things to worry about at that moment like the fact that he was under arrest and sitting inside a police van with his father Kalabhai Sarvaiya and thinking of committing suicide that night. The rest of his family - his mother, three brothers, their wives and six children - was absconding fearing arrest.

He says he was depressed and looking down at the floor of the vehicle. “I didn’t realize that the four boys who were being beaten were my nephews. I discovered it was them only after the court granted me bail and I returned home that night,” he says.

Piyush now wishes he had looked longer at the violent scene which got passed forward to millions of smartphones across the country and world, triggered the biggest Dalit agitation in the history of Gujarat; And, as some have argued, led to the resignation of Chief Minister Anandiben Patel.

“Had I known it was them, I would have broken from the police and run forward to help them,” he says, “But at that exact moment I was thinking about writing a suicide note like Rohith Vemula.” But after he heard about the attack on Balubhai and his four nephews, he changed his mind and decided to live and fight for them.

“My brother Lalji Sarvaiya was killed on September 13, 2012 in our village Ankolali. The Kolis burnt him alive inside our house. He was only 27,” Piyush suddenly reveals, “There were huge protests even then. Some of my relatives complain that the protests made the name Sarvaiya stand out even more.”

It’s past 11 pm now and many of the elders in the family are telling Piyush to get rid of me. They don’t understand why a reporter would hang around the village at such a late hour. Piyush says, “Now is not a good time...”

* * * * * * * * * *

The next day, Piyush arranges for us to meet at the house of Mangabhai Sarvaiya, his uncle, in the village of Mainn. One of Mangabhai’s sons, who lived in Mumbai for a few years, checks my ID card and Facebook account, says he has heard of the Hindustan Times and tells his father it’s safe to let me in.

Piyush is carrying a thick file of legal papers and newspaper clippings and starts from the beginning.

“We had a joint family of 14 and lived in Ankolali village until 2012. The majority were from the Koli (OBC) caste and we were the only Dalit family. But our financial condition was better than many Kolis even though we were considered untouchable in the village. All of us four brothers had motorbikes. We owned a bicycle repair shop, three buffaloes, 15 bighas of land. Not just some encroached forest land...we had the titles, a government water and electricity connection, a bore-well that cost Rs. 1.5 lakh. My brother, Lalji, who was killed, worked as a contractor in a stone quarry and earned nearly Rs. 30,000 a month. He had a great lifestyle and would always wear nice clothes and would never get on his motorbike without cooling glasses.”

“And I owned a horse. Showk se liya thha (Just for kicks). I would ride out to our fields and back on the horse like I was some Raja. I was the only guy in my village with a horse and I could see the Kolis hated me for it. My father would often scold me saying one day the Kolis would teach me a lesson. Instead, they taught my brother a lesson.”

Lalji Sarvaiya had done the unthinkable. He and a Koli girl had fallen in love. She was the niece of the most powerful man in the village - the Panchayat president’s husband.

Two days before Lalji was killed, the girl had gone missing from her home. According to her initial statement to the police, submitted before the Una court, the girl had said that she fled to Junagadh city to meet a lawyer for legal help. She wanted to marry Lalji. It will never be known if Lalji knew where his lover was on those two days or what she was planning.

“On the third day, when Lalji was home alone with our father, a mob of 500 Koli men surrounded our house. They first pelted stones at the house and injured the animals. Then they moved in. Doused Lalji with kerosene and lit a match.” When Lalji’s lover got to know about the murder, she dropped the lawyer and took refuge in a government-approved women’s shelter. Her letter, written to the management of the shelter, clearly mentions that her life was in danger and is part of the case records.

Eleven men, including the panchayat president’s husband, are still in prison. But the case took a sudden turn a few days before the July 11 Una atrocity. The girl changed her statement. Appearing before the court for the first time since the case was registered in 2012, she said that she did not know Lalji. She also denied that she had taken shelter in the women’s home and claimed that she was with her parents the day Lalji was burnt alive.

“She turned hostile because the police did not help her properly. The police brought her back to her parents’ house in the village a few days after the murder and she has been with them ever since. Sticking to her original statement would mean that her uncle would get convicted,” Piyush says.

A few days later, Piyush took his entire family to Gandhinagar and submitted a letter to the chief minister’s office, saying they would commit suicide if justice isn’t done. They also demanded land.

“After the murder, we never dared to return to the village. We sold our cattle and surrendered our house and farmland to the revenue department. We were given the official status of ‘refugees’ by the district administration and promised that we would be given the same extent of land in another village.” In the last four years, the government has surveyed many villages. Each time they would find a fertile piece, the local Patels, Darbars and Kolis would oppose the land allotment - a fact confirmed by the revenue officer in-charge of Una, G V Limbasia.

“In cases where there was no opposition, the land identified would be so poor that we would reject the offer,” Piyush says. They finally agreed to accept a poorly located housing plot in Delwada village.

“The plot is in a place that gets flooded every year. It is right next to 200 houses belonging to Kolis. But we accepted it because the farm they were giving us is fertile and not far from the housing plot.”

Delwada village offers a great example of how little difference there is between the BJP and the Congress at the grassroots level. Upper-caste loyalists of both parties jointly submitted a memorandum to the government opposing the farm allotment to Piyush’s family. They wrote they’d rather see a public hospital on the same spot. The local officials luckily took Piyush’s side but the state government appeared to have other plans.

“The housing plot is now in our possession but the farmland is waiting final approval by the chief minister for nearly two years. That’s why we threatened to commit suicide outside her office,” Piyush says.

The moment they returned to Una on June 24 after submitting the letter to the CM, the police arrested Piyush and his father under section 309 of the IPC that criminalizes attempted suicide. “The magistrate requested us to withdraw our threat and give an undertaking that we would not kill ourselves. It was ridiculous.”

“Will a man stop himself from suicide because he has given an undertaking? We refused and finally they were forced to release us on July 11, coincidentally, the same day Balubhai and my nephews were attacked by Go-Rakshaks,” Piyush says.

His uncle Mangabhai, who has sat quietly through this five-hour interview, starts laughing loudly. “Sarkar Gando chche (the government is mad),” Mangabhai says. “Don’t laugh. You do know that you need to be careful now, right?” Piyush tells his uncle, shutting him up.

* * * * * * * * *

Many of the Sarvaiyas are in the business of skinning dead cattle and do a basic curing of the hides, with salt and lime, before selling them to resellers, who then sell them to dealers from the leather factories in Kanpur and Kolkata.

Piyush’s uncle, Mangabhai Sarvaiya, is one of the most successful among the Dalits in the skinning-and-curing business. He has a big client from a Kolkata factory and one from Kanpur. He inherited the profession from his father who had it passed down to him through the centuries. But the business has become profitable in the last 10 years since mobile phones exploded on the scene and connected small operators like Mangabhai to the big players. He now even buys in bulk from smaller operators like Balubhai from Mota Samadhiyala and passes it forward for a cut. Today, he owns a large house, a Bolero pickup truck, an Alto car and a few motorbikes.

“I have around 30 villages under my control,” says Mangabhai, explaining how the business works:

People in the skinning business like him and Balubhai have to pay a bribe to the panchayat president of a village to collect cowhides from there. “If it is a big village, I pay as much as Rs. 40,000 to the president. For the next six months, every time a cow dies in the village, the president would call me to pick up the carcass,” he says.

That means around Rs 12 lakh in investments, how much does he make? “More like seven or eight lakhs,” he says bashfully, “In some smaller villages the bribe is only around Rs 5,000 for six months. We are a joint family and we make around Rs One lakh a month. More in some months like when there is drought or flood.”

“Why do you think I am asking him to be careful?” says Piyush. Mangabhai’s younger son has already had a close brush with a dominant-caste mob that was masquerading as cow protectors.

They tried to corner him a few months ago but he managed to zoom past them in the Bolero. “See, in most villages, the dominant-caste panchayat president, who we bribe, does not make as much money as we do. They are always pressuring us to pay more. They are also very jealous of us. There have been occasions when the president would have called us to pick the cow and then informed the go-rakshaks behind our backs,” Mangabhai says.

Piyush says, “Our people are willing to do any work from skinning dead animals to working in the fields and driving taxis in Mumbai. The Patels and the Darbars will never do these jobs. They always hire somebody. The landlords have had a few bad years (drought in 2013 and floods in 2015). Lots of cattle died and the only people who benefited were our people. Plus, many of our boys have gone to Surat to work as laborers in the diamond-cutting industry. Many of the Sarvaiyas are doing well. The dominant castes can’t stand our success.”

The feudal castes, Piyush says, are still sore over the mass protests that erupted across Saurashtra following his brother’s murder. “They thought nothing would happen but 11 men are still in jail because we now have good lawyers who are paid by Dalit NGOs. The name Sarvaiya now evokes instant hatred from the Kolis, Darbars and Patels here.”

In the last four years, Piyush has also become an Ambedkarite activist and goes to the aid of other Dalits fighting caste atrocities. When Dalit PhD scholar Rohith Vemula committed suicide at the University of Hyderabad in January, Piyush led a 200-motorcycle rally through all the villages in Una Taluk as a mark of protest.

“I changed my mind about committing suicide and leaving behind a radical suicide note because I thought I can be more useful if I am alive. Most of the people who first rose up and protested the (July 11) attack on Balubhai were from the Sarvaiya family. I had organised them.”

He says the police and intelligence agencies in Gujarat are still trying to figure out how such a massive agitation was built. “Many of us are under surveillance,” Piyush says.

Mangabhai’s family is not comfortable with letting us stay the night. Mangabhai’s son tells me, ”I have heard you haven’t spotted a single lion yet. Why don’t you sleep in Madhubhai’s farm in Khilawad village? It’s near the forest.”

* * * * * * * * * *

“My farm is not near the forest. It is in the forest,” laughs Madhubhai Sarvaiya over the sound of his motorbike, as we make our way to his land in pitch darkness later that night. He seems a little mad at first. He has made me hold a big torch. We skid and slide up a hillside that is oozing slush and I can barely keep my balance when he says, “Keep flashing the torch around.” What for? “There is a Singhni (lioness). If you are lucky, you might spot her.” Lucky?

“They are like my pet dogs. They know me. But no stranger can enter. It is like they guard my land.” I am a stranger, I say, but he only laughs that mad laugh again.

When we reach the highest point in these low hills, he flashes his torch on a bamboo frame and says, “That’s my macchan. We will spend the night there.” When we settle down to sleep on two cots that are precariously placed on the frame, he points to a hillock that’s about 300 meters away and says that an entire pride lives behind it. “One big lion and three lionesses with cubs.” From the macchan, we have to take turns all night to spray the farm with torchlight. The light stuns animals that try to graze on the land. Lions sometimes prey on these stunned animals. “We help the lions and the lions help us,” Madhubhai says.

The lions are the reason Madhubhai and his family have been able to keep this precious farmland for 25 years. Nobody else wanted to take the risk. When Madhubhai’s father quit working as a landless agricultural laborer and occupied this forest land, the lions were a lot more hostile. He took the risk because this is was the only way for him to get land.

Five years ago, the lions befriended a Koli family. They have started cultivating a patch next to Madhubhai’s. “These Kolis are among the poorest people in the village. Poorer than even us,” says Madhubhai whose younger brother now works in the Army. “But now, the rich Kolis, Darbars and Patels have their eyes on this part of the forest,” Madhubhai says.

Madhubhai’s family has already been getting informal warnings from the forest department about the encroachment. He believes that the forest officials are colluding with the dominant castes to oust him and grab his land. “It is happened all around Gir,” he says.

“All the land was once jungle. The dominant castes snatched the land away from the forest and killed the animals and the lions. Over time, they used their influence with the British and then the Indian governments to get titles for this encroached land. We don’t have the influence to get the titles in our name and killing lions is now illegal. So we just learnt to live like this. Now they want this land also.”

We spend two more nights sitting up on the macchan, talking politics, hoping to spot a Lion. Every night we hear one going “ooongh-ooongh” just a few meters away but can’t spot it.

It is the morning of July 30 and I must leave for Porbandar, the birthplace of MK Gandhi, where another Dalit family from a different sub-caste waits to share details of an atrocity committed on them. As we are sliding back on the motorbike from the farm to the village, Madhubhai stops to greet a man who is driving a three-wheel Enfield Jhakda up the slopes.

“You should take his details. He was also attacked by Go-Rakshaks while transporting a dead cow in January this year. He is also a Sarvaiya, my uncle,” Madhubhai says introducing Veerabhai Sarvaiya. Veerabhai doesn’t speak Hindi and I don’t speak Gujarati. Madhubhai does some basic translations.

‘Veerabhai was carrying the cow and driving up a slope when the Go-Rakshaks tried to stop him. He didn’t stop immediately and said he would park to the side once up the hill. He waited there for some time for them to catch up and when they did not come, continued on his way. Around 15 minutes later, a larger mob of gau rakshaks caught up with him in an SUV.”

“They beat him saying he did not stop when they asked him to. They also abused his relative Mangabhai from Mainn village saying he had become too arrogant with new money. His Jhakda was damaged and he was admitted in the hospital for 15 days. Since his attack Veerabhai Sarvaiya became an Ambedkarite activist. He too has stopped skinning cattle since the July 11 atrocity. He goes around the villages along with activists mobilizing Dalits for a massive agitation that’s planned in Una on August 15 Independence Day.

But were his attackers arrested? Are they still under arrest? What is the status of the case? Veerabhai has been assigned a government lawyer but hasn’t been kept informed about the developments. Madhubhai gives him my number saying he should call me after getting full details from his lawyer. It has been over a week. Veerabhai Sarvaiya hasn’t been returning my calls. Maybe, he too thinks I am CID.

Get Current Updates on India News, Election 2024, Arvind Kejriwal Arrest Live Updates, Bihar Board 12th Result Live along with Latest News and Top Headlines from India and around the world.