The golden age of victimhood

Barring impoverished tribal women, every group in the pyramid of Indian life is an oppressor or a potential oppressor. But they are also victims.

The true nature of an age is imperceptible most of the time. On occasion we see the fragments clearly, we see the ‘issues’, but the truth as always is in the assembly of the parts. We have suspected for some time now that we are in the golden age of organised compassion, which by another name is the age of victimhood, but what we may have missed is that it has infected all. We are, finally, a world filled with victims. Men and women and the ambiguous; blacks, browns and whites; paupers and millionaires; even billionaires (we will come to that); the oppressed and the oppressors, all victims. And nobody is lying. That much we can see in the rise of the new socialists and radical conservatives around the world. They derive their powers from hundreds of millions of people who claim they have been wronged by some dominant force. It appears that the whole world is awash with unprecedented humility.

If you do not believe you are a victim, you are probably arrogant, or it is just that you are yet to find the name of your group, your kind. Look carefully. Great compassion awaits you but to claim the consideration you must first prostrate before the world and accept your suffering. The age of the strong and silent has passed. These times belong to the fragile loud.

Barring impoverished tribal women, every other group in the pyramid of Indian life is also an oppressor or a potential oppressor, but they are also recognised, correctly, as victims. Dalits were victims long before the age of victimhood and urban compassion dawned. Brahmin students would say oppression is when you have scored 95% and cannot secure a seat in a university.

Affluent urban Indian feminists who as children received more opportunities than 99% of Indian males do believe, rightly, that they are victims too because of the nature of Indian society. Their husbands, brothers and fathers, too, are today recognised as modern victims. That is the inherent beauty of the age of victimhood and a phenomenon unique to our times. The upper-caste, rich, highly educated Hindu male has a claim to victimhood. His complaint is manifested in simple and complex ways. In the simplest terms he would say that the laws that are meant to protect women from sexual abuse or from her in-laws are so powerful that they terrify him. The elite Indian male, finally, is beginning to comprehend the miasma of discrimination. His more complex lament emanates from his perception of himself as an economic underclass. This view is similar to the modern western middle-class white male’s feelings of inferiority.

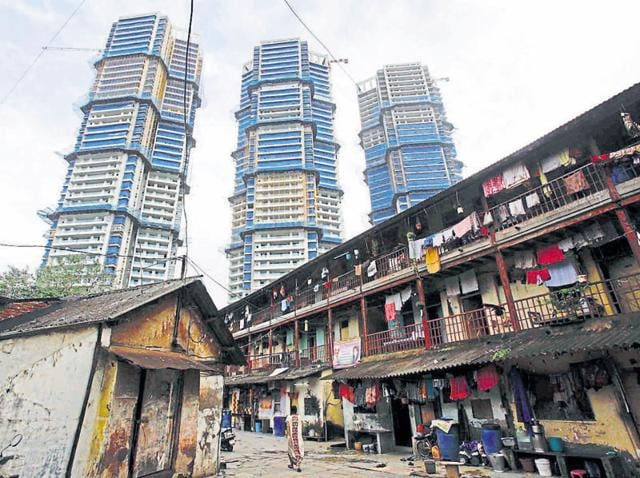

In the heart of the sudden moral war in the West against inequality is not the rage of the very poor, but of the middle class against the very rich. Across most major cities of the world the very rich have made prime real estate unaffordable to the moderately rich. In some places the very rich are displacing the mere millionaires. In South Mumbai too. If you listen to the millionaire entrepreneurs of South Mumbai talking about the very rich, you would think they sound a lot like Communists. They talk about the vulgarity of money, displacement and ‘we need inheritance tax’. And, there is the matter of Mukesh Ambani’s gargantuan home blocking the sea views of hundreds of millionaires, and reminding them of their smallness.

Also, in the hierarchy among elite Indian youth, employment is today subordinate to valuation-seeking entrepreneurship. What the enthusiastic media coverage of young Indian entrepreneurs in the new economy often misses is that their entrepreneurship, often, is not ‘great gambles’ but manifestations of privilege that come with elaborate safety nets.

The average upper-class Hindu male, standing many layers beneath the new high castes of wealth and enterprise, considers himself a victim of inequality.

Billionaires, too, consider themselves victims. But not the Indian variety, whose complaint that they are victims of the political system would elicit no sympathy. The victimhood of the rich men of Silicon Valley is more fascinating. To be precise, they anticipate their victimhood because they are used to anticipating everything. As they believe they are the peaks of human and intellectual evolution, they are not so threatened by humans as much as they are by machines. That is why some of the brightest minds of the Valley appear so irrational when they talk about the future of artificial intelligence and how the machines may one day colonise man.

The victim, who is today one of the most powerful concepts influencing politics, culture and economics, is real, was always real. He, or she, unlike the gods, was not the pure invention of ancient storytellers. But storytellers were enchanted by the idea of the victim. The proto-victim began life as the underdog in our stories, a character class who has not just survived the whole history of storytelling but thrived. It is now almost impossible to tell a glorious, captivating and moral story without the underdog whose progress towards justice or tragedy is what almost all stories are about.

It was inevitable that journalism would lift the idea of the underdog. The rise of modern activism, which is funded by trusts created by the excess wealth of capitalism, the tax structures of rich countries, including steep estate and inheritances taxes, and ideologies masquerading as philanthropy, has expanded the scope of victimhood. As groups of people gained their victimhood, and their laments were efficiently transmitted by journalism and the social media, similar sects and rival groups aspired to be so.

Have you, by now, found your wounds? If you still do not believe you are a victim, you are a part of such a minuscule minority that you are, by default, a victim of a majority in a glorious, perpetual crisis.

Manu Joseph is a journalist and the author of the novel, The Illicit Happiness of Other People

The views expressed are personal

The author tweets as @manujosephsan