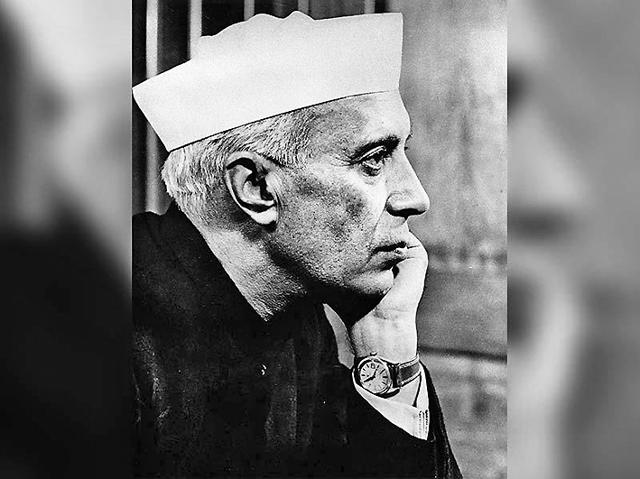

Nehru was a leader of shining veracity

Jawaharlal Nehru is not to be belittled. He is not to be eclipsed by the sawdust haze of idealism’s current drought

The Hindustani word or exclamation ‘arey’ is untranslatable. It could mean any or all of ‘but, oh…’, ‘oh, but wait…’, ‘just a moment…’, ‘incidentally…’, or simply, ‘also…’

Harivanshrai Bachchan’s translation of Robert Frost’s ‘Stopping by woods on a snowy evening’ is stunning. For the lines ‘But I have promises to keep/and miles to go before I sleep and miles to go before I sleep ’, the author of ‘Madhushala’ gives ‘Arey, abhi to milon mujhko, milon mujhko chalna hai’. The opening ‘arey’ captures the reader’s attention even more compellingly than Frost’s ‘But’. Jawaharlal Nehru’s transcribing of these lines in his own hand unsteadied by a stroke, with the poet’s first name charmingly mis-written as ‘Richard’, has enhanced the poem’s currency in India. That Nehru kept the extract by his bedside, his death-bedside, has tinged it with pathos. A few days ago the Hindi poem glowed anew in my mind when I came to read, in Rupert Snell’s captivating English translation (In the Afternoon of Time) of Bachchan’s autobiography, a description of the poet’s last visit to Nehru. The stroke, which had affected the left side of his frame, had slowed the PM down. Bachchan was walking a few steps behind Nehru in the Teen Murti House gardens as Indira Gandhi, holding her father’s hand, led him slowly forward, step by step. Dew lay over the grass and Bachchan noted, as a poet would, that Panditji’s right foot left footprints on the grass while the left foot drew a continuous line.

‘Arey, abhi to milon mujhko…’

What were the miles, arey, the many miles, that Nehru saw lying ahead of him? What was the task, partially finished or wholly unfinished, ahead ?

He was, like any of us, many things – parent, grandparent, brother, friend to many who, like Bachchan, were not in politics, and to many who were in that murky line, a reader of books, fond of stimulating conversations, of anything that showed personal courage like adventure, sports, a writer, thinker. But unlike us, also a politician who thought of politics as a form of idealism, an MP, Prime Minister…

In each of those roles, Nehru had miles to go. As a father he most definitely worried for his daughter’s future. Delhi is, after all, Delhi, the graveyard of empires where loyalties are strictly bound to power, where smiling pick-thanks drop affiliations on the road between office and crematorium, even turn hostile. And he agonised, surely, for the fatherless grandsons whom he adored, billeted in boarding school, bereft of disinterested elders to guide them or dependable ‘youngsters’ to give them unselfish company. As a brother of two highly but incompatibly intelligent sisters, he must have wished his family’s chemistry was less complex.

Read | Team to move high court against ‘saffronised’ textbooks

He must have doubtless worried about what would happen to his books, his papers, personal ones, those that were official and personal-official, a combination that forms itself and is impossible to unravel, his more intimate papers, those he wrote not in shaded secrecy but in honest privacy to chosen ones who having received them, had passed on.

In those weeks after his stroke and he would have also been troubled by memories, of the man to whom he owed everything and who wrote to him in blessing in Hindi ‘May you live many (bahut) a year and abide in those years as Hind’s only Jawahar’, extending the loop in the Devanagari ‘bahut’ to make it ‘bahuut’. How far, how very far removed from 1964, the Mahatma must have seemed to him. And he must have thought too, with some remorse, of his strained ties with Subhas Bose, with Sardar Patel, both gone into the mists. Equally, his out-of-joint-ness with Rajagopalachari’s dissenting spirit, Jayaprakash Narayan’s revolutionary ardour, Kamaladevi Chattopadhyay’s brilliant but neglected creativity. He may well have felt more than a pang of regret at his un-democratic dismissal of the Namboodiripad government in Kerala in 1959. And remorse of a very serious order over Sheikh Abdullah, friend of friends, comrade of comrades, being left by the most bizarre of inexplicable conspiracies, to the sharp needles of Kashmir’s lonely pines.

Read | Celebrating Nehru: A PM who saw India as tolerant and compassionate

Of these regrets, real and painful that all of them were, the most troubling, tormenting, has to have been the miles that lay, in unmapped confusion, to a solution to the Kashmir problem. The stricken Nehru must have asked himself where he went wrong.

And then, the five-letter word – China. How could a country he embraced when the powerful nations of the world were shunning it, treat India, his India, to war ? Where did that leave Panchashila, non-alignment ?

Beyond these Nehru must have been torn by deep anxiety over two other, life-defining things for India and therefore for its Prime Minister : one, the stubbornness of Indian poverty and two, the remorselessness of Indian bigotry. There can be no doubt that these thoughts would have beset his twilight mind.

But, stepping back from these tormenting thoughts, if Jawaharlal Nehru had looked at the India that he had indeed fashioned, he would have felt his fears giving way to pride. Contrary to the grim prognostications of the West, particularly of Great Britain, he would have seen that after three general elections India was a secure democracy, exercising freedom of thought and expression, of faith and of religious practices, with a press that was as courageous as it was unfettered, where politics was free from fear of the bully and the blackmailer, where the judiciary was independent and where life expectancy at birth was rising steadily, as was the age of the Indian girl at marriage. And above all, where science and technology were being harnessed for the nation’s good not for belligerent ambitions.

The architect of modern India was a human with human flaws and failures but a leader of shining veracity. And guts beyond the ordinary. Who but he could have turned to a group of bigots shouting ‘Mahatma Gandhi murdabad’ outside the house where the 79- year-old lay fasting, and demand in his matchless Hindustani “Who said that, who ? Let the man who said that kill me first…”

Read | Truth about Nehru: Why conspiracy theorists are wrong about him

I am not sure if he used “Arey…” to preface his chastisement. But something of that two-syllabled admonition was most definitely heard because the murdabadis just slithered away.

Nehru is not to be belittled. He is not to be eclipsed by the sawdust haze of idealism’s current drought.

Gopalkrishna Gandhi is distinguished professor of history and politics, Ashoka University. The views expressed by the author are personal.