Communal riot and inter-ethnic tapestry of cities

A city is never the same after a communal riot or pogrom; it does not completely heal, it does not go back to being quite the tapestry it used to be

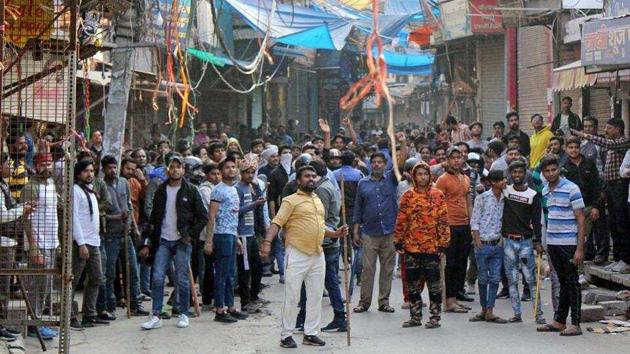

Stories and images from the communal violence in Delhi over the last three days have been gruesome, chilling and a throwback to similar social fabric-ripping times in other cities in the past. Whether it was Delhi in 1984, Bombay in 1992-93, Ahmedabad-Baroda in 2002, Mangalore last year, the modus operandi is strikingly similar.

Real or imaginary grievances are framed in a deeply polarising manner by politicians, provocative words or acts follow, these elicit an angry and violent response from those targeted, which then escalates into a full-blown riot or, worse, a pogrom. But why are some cities prone to this? What happens to the violence-hit cities after the embers die down, the dead are counted and others listed as “missing”?

In north-east Delhi, the embers are still raging hot, the dead are being counted at 20 and more, the Delhi high court had to be beseeched to allow ambulances to and from certain hospitals and for the police to consider filing FIRs against those like BJP leader Kapil Mishra whose speech allegedly triggered the violence.

The stories are horrific — a boy with a drill machine through his head, a passer-by who was very nearly lynched, an Intelligence Bureau official who was presumably stuffed into a drain, a cop who took bullets, shops selectively vandalised, women screaming in fear as their homes were attacked, mobs screaming in glee as their message hit home, and more. Homes and shops marked out with saffron flags for safety, journalists attacked and repeatedly asked for their religious affiliations, cops being attacked with stones, cops giving cover to one mob, the injured brought to hospitals with injuries from a strange acid-like substance.

There was violence from both sides but reports show that the scale, intensity and viciousness against Muslims were spine-chilling. This also showed up the limitedness of Arvind Kejriwal’s politics; “Jai Sri Ram” politics cannot be countered with sparkling schools and Hanuman Chalisa. Home minister Amit Shah should have resigned, he did not.

When and how did the anti-Citizenship (Amendment) Act protests spiral to a communal riot or, as political scientist Prof Ashutosh Varshney commented on social media, begin to look like a pogrom? There is, he remarked, “enough evidence” of the police looking on instead of acting neutrally as mobs went on a rampage and sometimes aiding violent mobs for it to be called a pogrom. Can the state be shamed into action? This state, Varshney argued, cannot be shamed into action because “it is unambiguously anti-Muslim”.

His observations apart, it is his decade-long depth study of Hindu-Muslim riots turned into the ground-breaking book “Ethnic Conflict and Civic Life” more than 15 years ago that offers a perspective to urban communal violence. Varshney draws on research of three pairs of cities — one in each pair a communally volatile and riot-prone while the other relatively peaceful — to arrive at his central argument that communal violence — or peace — is largely determined by the civic life of communities in question; that if civic engagement was inter-ethnic rather than intra-ethnic, conflicts are less likely to spiral into widespread violence.

Increasingly, Hindus and Muslims in the same city or same area of a city lead different, silo-like and often mutually antagonistic and ghettoised lives. The many stresses of urban life make these antagonisms worse. And politicians then play on them, mine the insecurities and plant red flags. Inter-ethnicity is what the BJP has assiduously tried to damage.

What’s worse is that after such vicious violence, civic engagements suffer. There’s more — not less —ghettoisation. This means the ground has been laid for another round of communal strife, riot or pogrom in the future when politicians seek to profit from it. A city is never the same after a communal riot or pogrom; it does not completely heal, it does not go back to being quite the tapestry it used to be.