Food: How risotto is just khichdi and other culinary tales

Natasha Celmi

Oct 17, 2021 12:10 AM IST

An Indian foodie married to an Italian man writes about how Indian and Italian cuisines are better partners than we think

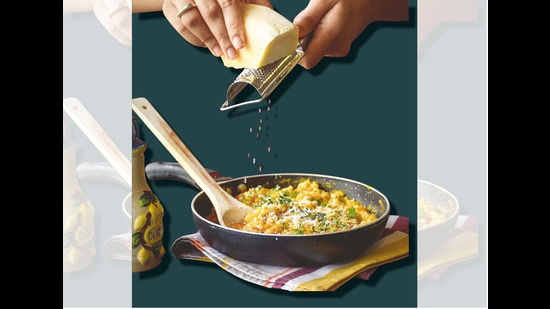

I am Indian and my husband is Italian, but the kitchens we grew up in? They’re much the same. For example, although the students at one of my cooking workshops laughed at me for killing the romance of a risotto by comparing the consistency to our desi khichdi, the concept of both dishes is the same—raw rice cooked and another significant element, cooked with a fluid consistency that allows every grain to remain separate.

Are you a cricket buff? Participate in the HT Cricket Quiz daily and stand a chance to win an iPhone 15 & Boat Smartwatch. Click here to participate now.

Catch your daily dose of Fashion, Health, Festivals, Travel, Relationship, Recipe and all the other Latest Lifestyle News on Hindustan Times Website and APPs.

Catch your daily dose of Fashion, Health, Festivals, Travel, Relationship, Recipe and all the other Latest Lifestyle News on Hindustan Times Website and APPs.

Share this article